Early Language Matters by Louise Packness

In an undergraduate communications class I was taking at Hunter College in NYC, many years ago, we were shown videos of Washoe the chimpanzee learning American Sign Language. (ASL) I was mildly interested in attempts to determine primates’ ability to learn language. But my real focus in these videos and in this class was American Sign Language itself.

I was taken with how “expressive” I found the visual-gestural language of the Deaf community. Peoples’ facial expressions were animated. There were large and small, fast and slow gestures and body movements. Eye contact was vital. I became consumed with questions about different forms of language. Could it be that a language that was expressed visually was somehow more “honest”, more “direct”? Certainly I had experienced misuse of spoken language: twisting of phrases and words; verbal manipulation of a sort. Could ASL use by-pass abuse of speech and more easily get to the heart of an issue? I felt compelled to explore this issue. I already loved language related learning, I.e., foreign languages, the origin of language, how languages change over time – and the nitty gritty of speech sound production as well as grammar and morphology and syntax.

I went on to graduate school and became a Teacher of the Deaf. I got my answer. ASL can be used in a manipulative way just the same way a spoken language can be. A visual gestural language may look more “immediate” and “‘direct” – “honest “if you will. But ASL is a full and true language; it follows rules, has exact vocabulary, word meanings, sentences and syntax and it is entirely possible to be false and manipulative in the visual-gestural form as well as the spoken language.

In my deaf education teacher training, the question of language acquisition for deaf and hard of hearing children born in to a hearing world came to the forefront. How do deaf children learn language and how do they learn to think? I went to study language acquisition of both deaf and hearing children and speech language development has been my professional work for 35 years.

In general conversation, we often talk about communication and language interchangeably. They absolutely overlap; communication is a form of language and language is a part of communication, but they are not entirely the same.

Communication starts the moment a baby is born. It is about connecting emotionally with other living beings. We humans are hard-wired to make and find comfort in these connections and we are born with a set of innate emotional expressions and an instinctive understanding of other people’s emotions. We express joy, sadness, fear, disgust, interest, surprise anger, affection and more, and recognize them in others.

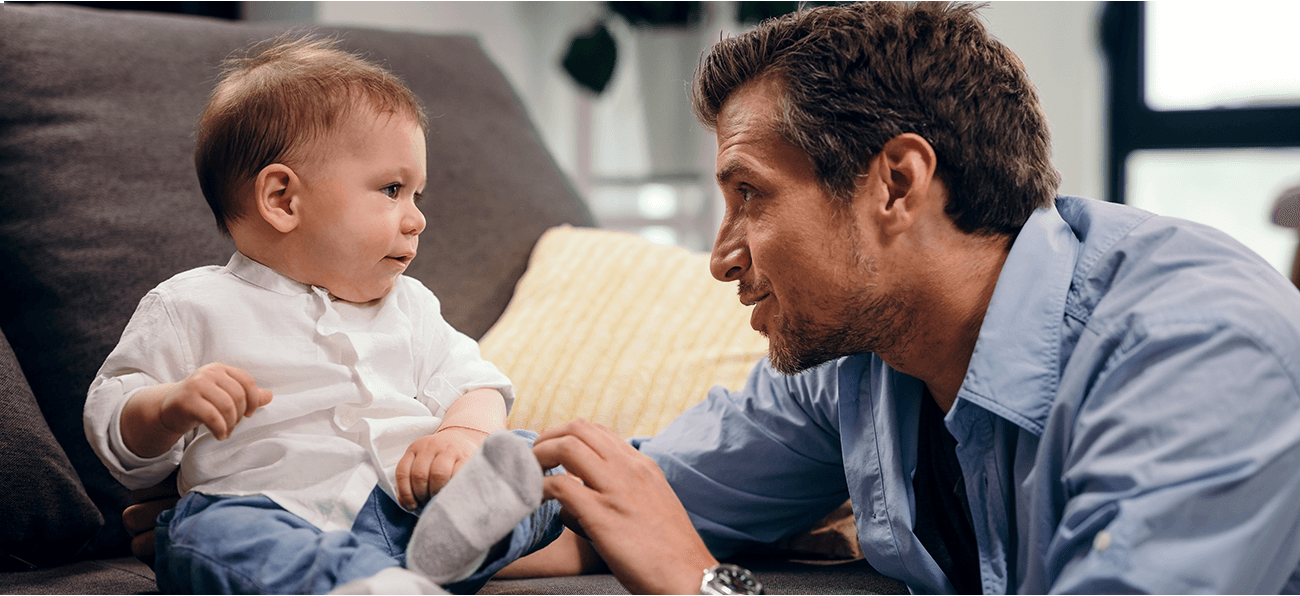

These early non-verbal connections are shared through vocalizations, facial expressions, and physical movements. Adults and babies engage in looking at each other, copying each other, taking turns on an emotional level – interactions known as “serve and return”. They are recognized by psychologists as important in shaping brain architecture in powerful ways, and helping to create a strong foundation for future learning. These interactions, conversations back and forth of sounds, gestures, facial expressions, tones of voice, eye-contact, posture and use of space give the young child a sense of belonging and are important to both partners.

Verbal communication, language, is also hard wired in the brain.

It is a rich, complex, adaptable system with rules; it is the way in which we combine sounds, create words and sentences in speech, signs and later writing to communicate our thoughts and understand others.

Verbal language provides us with the tools to know what we think and want, and understand others’ thoughts and wants. We need language to socialize and learn. Through both communication and language, we are able to learn new information, engage in rich pretend play, solve problems, ponder, invent, imagine new possibilities, and develop literacy.

Verbal language develops over time and follows universal, developmental milestones. Children learn at different rates, but there is a critical period in which a child must experience and develop language for it to develop fully.

None of us remember how we learned language. For the child with no interfering cognitive or physical challenges it seems that it simply happens. It is “caught” not “taught”. It is “caught” when a child is immersed in a world with caring adults who talk and interact and engage with this child. The particular language – or languages – a child masters is the one that the child experiences and has the opportunity to practice.

Language learning requires no tools or training – only these conversations.

When we say that early language matters it is the early, emotionally attuned engagement between adults and young children that matter.

When an interested adult is fully attending, talking and listening – making it easy for the young child time to start conversations; responding with interest to what the child is expressing with or without words, talking about those things the child is interested in at a level the child can understand, having conversations that go back and forth a number of times – these behaviors promote the natural development of language.

My work has been with children with special needs who have speech and language delays and disorders. For these children specialized early intervention is extremely important. The earlier the better to take advantage of a young child’s developing body and brain.

For the typically developing child, however, if language develops easily and naturally, what can interfere??

How strong children’s language skills are affected by their surroundings. Challenging environmental circumstance, such as food insecurity, poor housing, lack of health care, no access to books make a difference in the young child’s development; an adult, parent or caretaker who is not able to sustain attention or be attuned to the child makes a difference in the child’s development. When the adult is highly distracted – perhaps by troubling personal concerns or the ever-increasing interruptions caused by technology; i.e., needing to check Face Time, take a phone call, look at Instagram, check notifications, etc., the child is adversely impacted. The tremendous value of on-going conversations gets lost with many interruptions. Being aware of the factors that are challenging, we can begin to address them.

The early conversations are what matter. They say that a good conversation is like a good seesaw ride; it only happens when each partner keeps taking a turn.

Louise Packness,

Speech-Language Pathologist, M.A. CCC-SLP

Books and Resources for Early Language Matters

American Speech-Language Hearing Association: articles and books. Including:

– Activities to Encourage Speech and Language Development

– How Does your Child Hear and Talk?

– Apel, Ken & Masterson, Julie, J. Beyond Baby Talk: From Sounds to Sentences – A Parents Complete Guide to Language Development, 2001

Early Years Foundation Stage, (EYFS) Statutory Framework- GOV.UK

2021 Development Matters in the Early Years.

Eliot, Lise, What’s Going On in There? : Bantam Book, 1999

Galinsky, Ellen. Mind in the Making: Harper-Collins, 2010

The Hanen Centre Publications. Helping You Help Children Communicate.

– Manolson, Ayala, It Takes Two To Talk: The Hanen Early Language Program ,1992

– Parent Tips

– “Tuning In” to others: How Young Children Develop Theory of Mind

Lahey, Margaret. Language Disorders and Language Development: Macmillan Publishers, 1998

Lund, Nancy & Duchan, Judith. Assessing Children’s Language in Naturalistic Contexts: Prentice-Hall, 1988

National Association for the Education of Young Children (NYAEC)

Articles

– Reinforcing Language Skills for Our Youngest Learners by Claudine Hannon

– 12 Ways to Support Language Development for Infants and Toddlers by Julia Luckenbill

– Big Questions for Young Minds, Extending Children’s Thinking. 2017

Princeton Baby Lab. A Research Group in the Dept. of Psychology at Princeton studies how children learn, and how their incredible ability to learn support their development. 2022 babylab@princeton.edu

Pruett, Kyle,D: Me, Myself and I: Goddard Press, 1999

Ratey, John,J. A User’s Guide to the Brain, Vintage Books, 2001 : 253-335.

Rossetti, Louis,M: Communication Intervention, Singular Publishing, 1996

Siegel, Daniel J,& Hartzell, Mary. Parenting from the Inside Out: Penguin Group 2003